This content contains affiliate links. When you purchase through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Over the past year, we’ve seen how important science communication is to people on a large scale. Over the past year, we’ve all heard about masking and mRNA-like vaccines. A very important part of science messaging is illustration, creating visuals of science concepts. This includes everything from presenting an anatomical model of skin to charts and graphs of COVID-19 infections. These illustrations help make sense of science and even hopefully inspire a person to learn more. I contacted two designers, John Barnett and Marnie Galloway, who have illustrated scientific concepts in books and articles.

John Barnett and Marnie Galloway

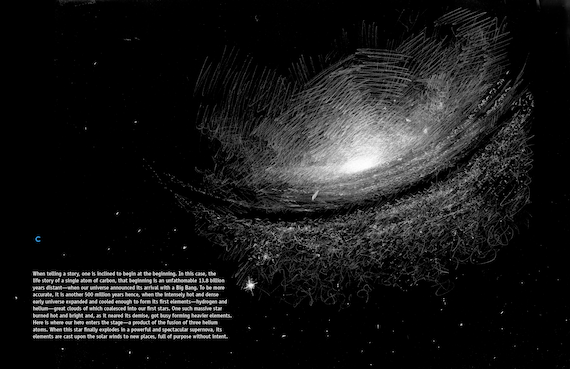

John Barnett recently published Carbon: the odyssey of an atom (May 2021) explores the incredible journey of a carbon atom from the beginning of the universe through smoke and animals on earth. In the introduction to the book, he explains that he was impacted by reading Primo Levi’s The Periodic Table, especially the last story titled “Carbon”. Primo Levi was the first science communicator he met.

Marnie Galloway has worked for several children’s magazines, including Muse and Cicada, illustrating a variety of scientific concepts. Through his work with Muse and Cicadashe is now an illustrator with Ellen Braaf at “Ask Ask”, a science column in the children’s magazine Ask.

how they started

I asked them both how they decided to do science illustration. After reading the periodic table, Barnett knew he had to do something based on the story one day. But he did not know how to make the project a reality. But when he had children, he discovered that they asked a lot of “fundamental questions”. For example, why do wood and metal look different on the park bench when exposed to direct sunlight? Besides, he wasn’t impressed with their science lessons. Although he was not a formally trained scientist, he taught himself through books and started working on the book. It also received excellent feedback from friends and acquaintances who were scientists.

Galloway explained that she began to Musea mid-level science magazine, and Cicada, a YA literary magazine that is no longer in print. When the serial “Ask Ask” artist quit, she was one of three or four artists invited to present. She designed new characters (a chipmunk and a pigeon) and submitted a sample comic.

“My pitch was selected and since then I’ve been doing the comic every month!” she says.

Make the abstract understandable

One of the most important tasks for science illustrators is to make concepts understandable for multiple audiences. While Barnett does not think of Carbon as a children’s book, it wanted to communicate the concepts to the public. He said: “One thing I didn’t want to do was draw too many microscopic things. I wanted it to be quite tangible like there was a rock, water or a hawk. He didn’t want it to get too abstract.

Galloway’s biggest challenge is hooking young readers. She works “to tempt them with at least one big, fun sign that will pique their curiosity and inspire them to read the whole comic.” She has her 5-year-old son as her first reader “who looks over my shoulder when I’m working and lets me know if the comic is funny enough, if a visual joke needs to be worked on in the studio. Ask is such a big magazine, I always want to make sure my comic is up to par.

Know what to illustrate

For all illustrators and artists, they have to make a decision about what to illustrate in their work and what to leave out.

When asked how Galloway decides what to illustrate, she explains that it depends on having a great relationship with the writer, Ellen Braaf. Galloways says Braaf and editors discuss which information is best communicated visually and which information is best presented through clear, direct explanations. However, she has some leeway.

“Sometimes when I present the comic, I find that I have more space than usual to indulge in additional visual explanation, or that the text takes up too many square centimeters and I have to give up a great suggestion for a visual explanation,” she said. . “It’s such a well-oiled machine that I very rarely have to suggest changes to strengthen the comic beyond the script provided to me.”

As for how he decided what to show in Carbon, Barnett said: “Primo Levi has laid down a map. I wanted to follow this part quite closely. Some are obvious [like the] Peregrine Falcon.”

Barnett wanted full-page illustrations with no copy at all. At one point in the book, carbon has “become part of carbon dioxide again, and it just roams the planet… At this point, I don’t have to stick to a linear narrative. I’m going to use three boards in two different places where it’s like the carbon is an eyewitness to part of the planet. He wanted to show beautiful things about the natural world, from polar ice caps to deserts. But he also said he wanted to show some of the human interference in it somehow.

Each image is accompanied by a chemical equation, which helps reinforce the image with the science behind it. Barnett explains, “Chemical equations are there to remind you that there is still this microscopic thing and structure. And there is this C, again, this same C.

What they learned from the job

Galloway isn’t just a science illustrator; She’s an award-winning cartoonist with In sounds and seas and other works. I asked how his work on scientific concepts had influenced his other work. She says she has always been “a living room science enthusiast”, she often draws her scientific and natural interests “as a springboard for metaphor and meaningful emotional connections”. For example, she says, “When my firstborn was a few months old and I was up all night with him, I saw a linked post on Twitter that scientists had recently discovered that trees were sleeping. C It was both fascinating and deeply infuriating to read that the trees slept more than me! This knee-jerk emotional reaction was the basis of my comic Terrier.”

Ultimately, she discovered that her “creative process often begins with researching something far removed from my life and expertise to get out of my head, and often that research question jumps out of my curiosity about the world. natural”.

Barnett wanted to show the relationships in our world. For example, he says, “A fig leaf when you get close enough to it has real texture. Some of these things are starting to look different, but there are patterns that are happening. When you move the scale or squint, you might think to yourself, “Oh, that smoke kinda looks like water or those patterns in the city streets almost look like that fig leaf.”

Barnett also explained that he suffered from a degenerative eye disease and was slowly losing his sight. This was part of the recent motivation to do Carbon. But as a result, he says, “I’ve really slowed down and looked at things more carefully. And so I think that’s helped me. I see things like [the pattern in] the end sheets of the book. They are rotting logs that I walked on at least once a week. I find patterns and beauty in it; I’ve seen that tree rot for a few years now… It’s a lot of watching carefully, which I don’t anymore. And I think there’s legitimately an element of that for me, trying to kind of memorize those things visually, because I think I might not always be able to see them. But if I look at it so closely, and draw it for two weeks, these crazy patterns, I will never forget it.

This book will certainly help the reader see these incredible patterns, big and small, in everyday life.

A little more

When I asked Galloway what was her favorite thing she had illustrated, she replied, “My favorite comic was answering the question, ‘why do animals have tails?’ Learning to draw a hippopotamus with its tail spinning in circles to distribute its poo territorially was a highlight of his career! My children have never been so proud.

It’s just a taste of how two designers approach science illustration and why it’s such a fun and important part of comics and design.

Want more science illustrations? Check out Rioter’s list of 11 non-fiction science comics for adults. See this discussion on picture books for teaching science.